OCR in transition: How machine learning has opened up new possibilities

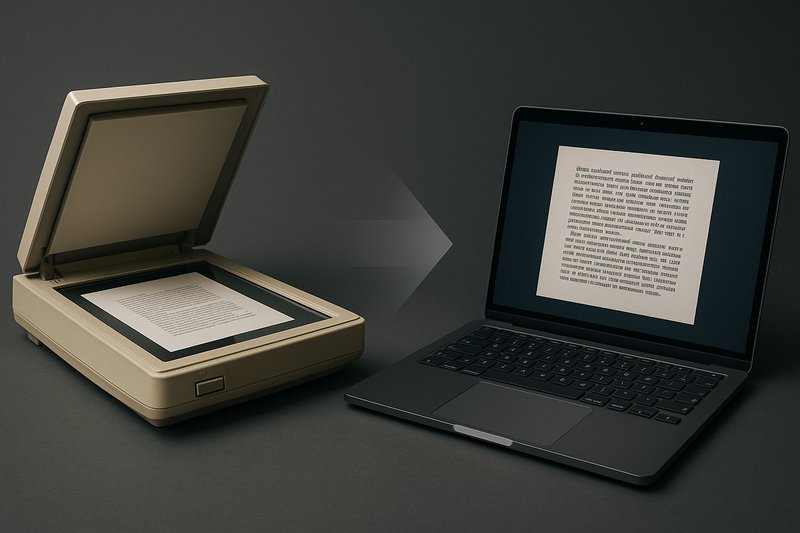

Text recognition was one of the first practical problems in computer vision and was solved for a long time using classic, rule-based methods. It was only with the advent of statistical models and later artificial neural networks that the field began to change fundamentally. While traditional methods are based primarily on fixed rules, thresholds, and geometric features, machine learning is based on data: the system learns what characters look like instead of analyzing them based on defined characteristics.

However, the transition from traditional OCR to ML-based OCR was not abrupt. Rather, the field evolved over several decades. Each new generation of models brought its own strengths and limitations, and many of the insights gained in the early years continue to have an impact today. Looking back, it is clear how strongly the different technologies influenced each other—and how this led to the development of the modern OCR systems used in research and industry today.

The early years: statistics and pattern recognition

Before neural networks became widely used, researchers focused on statistical and probabilistic approaches to character recognition. In the 1980s and 1990s, methods such as k-nearest neighbors, hidden Markov models (HMMs), and support vector machines dominated scientific literature.

HMMs in particular played a major role, especially in handwriting recognition. Research such as that conducted by Rabiner (1989)¹ laid the foundation for sequential models that could analyze not only individual characters, but entire character strings. The idea behind this was that the context of a character helps with recognition. This was particularly advantageous for handwritten texts, where shape and size vary greatly.

At the same time, feature descriptions were developed specifically for machine learning processes. Processes such as HOG and SIFT were not only used for object recognition, but also found their way into OCR research. This combination of ML classifiers and visual descriptors gave rise to the first hybrid systems that used both statistical and geometric information.

The influence of early neural networks

Even though deep learning only became popular much later, researchers were already experimenting with neural networks in the 1980s and 1990s. Probably the most important milestone in this phase was the development of convolutional neural networks (CNNs) by Yann LeCun and his colleagues.

Their model, known as **LeNet-5**, was introduced in 1998² and was originally developed for recognizing handwritten digits on American checks. Although LeNet seems small from today's perspective, it was a significant step toward end-to-end learning systems. For the first time, a neural network could learn directly from pixels without the need for handcrafted features. Many of the concepts introduced at that time—convolutions, pooling, layer-by-layer structure—still form the basis of modern models today.

Despite its significance, LeNet did not initially catch on outside of research. One reason for this was technical limitations: the computing power of the hardware at the time was not sufficient to train larger neural networks in an acceptable amount of time. As a result, the practical use of neural networks in OCR was initially limited to selected tasks, while classic ML models continued to dominate.

The path to deep learning: advances in data, hardware, and algorithms

It was not until around 2012 that the situation changed fundamentally. With AlexNet's breakthrough in the ImageNet competition, it became clear that deep neural networks were capable of solving large visual problems significantly better than traditional methods. This success was no coincidence: powerful GPUs, large data sets, and new training methods suddenly made deeper models practical.

These developments also influenced OCR research. Instead of classifying characters individually, researchers began to model entire words or lines of text directly.

An early example of this is the CRNN (Convolutional Recurrent Neural Network) model developed by Shi et al. (2016). It combined CNNs for visual feature extraction with recurrent networks (LSTM) that interpreted the text sequentially. This resulted in OCR systems that could no longer recognize isolated characters, but rather coherent text sequences – a decisive advance for complex scenes and unstructured documents.

Connectionist Temporal Classification (CTC), developed by Graves et al. (2006), also became a central component of modern OCR models. CTC made it possible for the first time to recognize text sequences without explicit segmentation. This means that the system no longer needed to know where one character ended and the next began—it learned this directly from the data.

This development eliminated many of the challenges associated with traditional OCR pipelines, particularly the need for clean segmentation. Deep learning models could be trained directly on raw images and learned structures, distances, and variations independently.

From symbols to words and entire scenes

Parallel to research in document analysis, interest in OCR grew in real-world environments—for example, in photos, street scenes, videos, or industrial recordings. So-called "scene text recognition" became a field of research in its own right.

Studies such as Jaderberg et al. (2014–2016)⁶ showed that neural networks can interpret not only handwritten or printed documents, but also text in complex environments. Skewed signs, busy backgrounds, or perspective distortions—all of these became increasingly manageable thanks to deep learning.

OCR thus left the purely document-based world and became one of the central applications of modern computer vision.

Modern text recognition methods: From deep learning to specialized models

With the breakthrough of deep neural networks, the way OCR systems are structured began to change fundamentally. While classic approaches could only recognize text after it had been segmented, models developed over time that automatically locate and interpret text in images. This development led to OCR increasingly being viewed as a holistic problem, in which localization and recognition are no longer processed separately, but rather in a common model.

An important step in this development was the emergence of deep learning-based text detectors. These models focus on reliably identifying text regions in images, regardless of whether they are printed documents, street scenes, product packaging, or technical surfaces. One of the early and highly acclaimed approaches was the EAST model (Efficient and Accurate Scene Text Detector), presented by Zhou et al. in 2017. EAST showed that text in images can be reliably localized without complex preprocessing steps or time-consuming segmentation. Instead of analyzing pixel clusters or edge structures, the model learns directly from training data what text regions typically look like.

Shortly thereafter, other models followed that further shaped the field. In particular, the CRAFT model by Baek et al. (2019)⁸ became a widely cited approach because it analyzed not only whole words, but also the relationships between individual characters. This enabled it to deliver stable results even in difficult situations, such as irregular spacing or oblique perspectives. CRAFT recognized how characters are spatially related, thereby establishing a connection that was previously only possible through handcrafted rules.

DBNet (Liao et al., 2020)⁹ ultimately added another milestone. The model relied on differentiable binarization, which made it possible to separate text regions with particular consistency and precision. This idea took up the central step of classic OCR—binarization—but integrated it completely into the neural model. As a result, many of the preprocessing steps that were previously necessary were taken over directly by the network.

Parallel to detection, recognition itself also continued to develop. Instead of classifying isolated characters, modern models increasingly focused on recognizing entire word or text sequences. Sequence models such as CRNN and methods based on Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) made it possible to consider not only individual characters, but also their context. The importance of this context can hardly be overestimated: in many cases, the interpretation of a character depends on which character comes before or after it. A simple example is similar shapes such as "O" and "0," which can have completely different meanings depending on their surroundings.

The introduction of Connectionist Temporal Classification (CTC) had a particularly significant impact on the field. This method, which was originally developed for speech recognition, made it possible to recognize text sequences without having to know the exact boundaries between individual characters. Instead of forcing explicit segmentation, the model implicitly learned where characters begin and end. This significantly mitigated many of the challenges of traditional OCR pipelines, such as overlaps, mergers, and irregular spacing.

Over time, the models evolved toward end-to-end trained systems. The idea behind this was that instead of manually defining many individual steps, a single model should simultaneously recognize where text is located and what exactly it says. This development was accelerated by advances in architecture research, in particular by the increasing importance of transformer models. Since the success of vision transformers, it has become apparent that self-attention—the core principle of these architectures—is particularly well suited for processing complex visual sequences.

OCR models such as TrOCR (Li et al., 2021)¹⁰ or Donut (Kim et al., 2022)¹¹ use this architecture to generate text directly from images, in some cases without the use of traditional bounding boxes. This means that the boundaries between detection and recognition are becoming increasingly blurred. Instead of breaking pixels down into regions that are then interpreted, the model generates text output derived from the entire image context. This opens up new possibilities for unstructured documents, forms, or scene images, as many of the previous design decisions no longer need to be made explicitly.

This development clearly shows how OCR has evolved from a series of tedious sub-problems to an integrated, learning-based process. Today, models perform many of the tasks that used to be defined in long processing chains. At the same time, the fundamental challenges remain: text can be skewed, distorted, covered, or poorly exposed. But unlike traditional methods, a deep learning model can anticipate these variations through training instead of treating them with explicit rules.

Current developments and the role of modern ML models in OCR research

While deep learning has fundamentally changed OCR over the past ten years, the field continues to undergo rapid development. New model architectures, larger data sets, and changing requirements mean that scientific questions are also constantly shifting. This is particularly evident in the increasing importance of multimodal models, which can not only recognize text but also interpret complex document structures.

A major topic of current research is the question of how neural networks can deal with increasingly variable forms of text. Today, text appears not only on documents, but also on packaging, machines, displays, road signs, and digital user interfaces. The boundaries between document-based OCR and scene-based text recognition are becoming increasingly blurred. Models such as Donut and TrOCR show that text is no longer viewed in isolation, but as part of a larger visual context. As a result, OCR is beginning to move toward complete document or scene understanding systems.

At the same time, the field is experiencing a strong convergence with developments in large multimodal models. Research projects such as Donut¹¹, LayoutLM¹², PaLI¹³ and Pix2Struct¹⁴ are investigating how layout information, image features and language can be processed together. Instead of simply extracting text, the focus is on the meaning of this text in the overall context. For structured documents, forms, or reports, this means that machines are increasingly able to recognize roles, relationships, tables, or hierarchies. In this context, OCR is no longer the end product, but an intermediate step in a larger understanding process.

Despite these advances, some challenges remain. Variations in fonts, severe distortions, or low resolution continue to be difficult to overcome. Many systems require large amounts of annotated data to function reliably, which is only available to a limited extent in some areas. However, research findings from recent years show that data-poor approaches such as self-supervised learning or synthetic data generation are becoming increasingly important. Work such as SynthText or the use of generative models makes it possible to artificially generate training data to cover rare or difficult-to-access text situations.

The issue of robustness is also coming into sharper focus. Under certain conditions, ML-based OCR models can be susceptible to adversarial interference, or they can deliver unpredictable results in cases of poor image quality. Studies such as those by Wang et al. (2020) show that even small changes to text images can influence a system's output.¹⁵ At the same time, however, there are approaches that attempt to make models more robust—for example, through augmentation strategies, ensemble methods, or special regularization techniques.

It is also interesting to see how interpretability has developed. Classic OCR methods were easy to understand: the results could be explained by rules, thresholds, or geometric features. With deep learning models, this is less obvious, which poses a challenge in some areas, such as regulated industries or document archiving. Therefore, part of the current research is devoted to explainable neural models and the question of how visual decision-making processes can be made visible.

Overall, a look at modern research shows that OCR is no longer an isolated topic. It is part of a larger spectrum of tasks revolving around visual understanding, multimodal analysis, and automated information processing. While manually defined methods used to form the backbone of text recognition, learning-based models have taken over this role—and continue to evolve at a rapid pace.

Conclusion: A technology in constant motion

Machine learning has profoundly changed text recognition. What used to consist of many individually defined steps is now increasingly being taken over by models that learn directly from data and independently capture complex relationships. From early statistical methods to the first CNNs to today's transformer models, this development is not only technically exciting, but also shows how closely research and practical applications are intertwined.

While traditional OCR continues to be used in specific, well-controlled environments, ML has opened the door to more robust, versatile, and context-sensitive systems. Modern models not only recognize characters and words, but increasingly understand entire documents, layouts, and scenes. This trend suggests that OCR will become even more integral to multimodal systems in the coming years—systems that analyze images, text, and structure together, enabling a new level of automated information processing.

Development is not complete. New models, larger data sets, and improved training methods will continue to push the boundaries of today's systems. But even now, it is clear that machine learning has not only expanded OCR, but completely redefined it.

References

¹See. Rabiner – A Tutorial on Hidden Markov Models and Selected Applications in Speech Recognition, 1989

²See. LeCun et al. – Gradient-based learning applied to document recognition (LeNet-5), 1998

³See. Krizhevsky, Sutskever & Hinton – ImageNet Classification with Deep Convolutional Neural Networks, 2012

⁴See. Shi, Bai & Yao – An End-to-End Trainable Neural Network for Image-Based Sequence Recognition, 2016

⁵See. Graves et al. – Connectionist Temporal Classification: Labelling Unsegmented Sequence Data with Recurrent Neural Networks, 2006

⁶See. Jaderberg et al. – Synthetic Data and Artificial Neural Networks for Natural Scene Text Recognition, 2014–2016

⁷See. Zhou et al. – EAST: An Efficient and Accurate Scene Text Detector, 2017

⁸See. Baek et al. – CRAFT: Character Region Awareness for Text Detection, 2019

⁹See. Liao et al. – DBNet: Real-Time Scene Text Detection with Differentiable Binarization, 2020

¹⁰See. Li et al. – TrOCR: Transformer-based Optical Character Recognition with Pre-Trained Models, 2021

¹¹See. Kim et al. – Donut: Document Understanding Transformer without OCR, 2022

¹²See. Xu et al. – LayoutLM: Pre-training of Text and Layout for Document Image Understanding, 2020

¹³See. PaLI: Scaling Language-Image Models, Google Research, 2022

¹⁴See. Lee et al. – Pix2Struct: Screenshot Parsing with Vision-Language Models, 2023

¹⁵See. Wang et al. – Towards Adversarially Robust Scene Text Recognition, 2020